- Home

- Camp Wolters

- A Model Soldier

- Camera Trip Through Camp Wolters

- Camp Wolters Longhorn

- Camp Wolters Ephemera

- Camp Wolters Guide

- Camp Wolters IRTC

- Camp Wolters Postcards

- Camp Wolters Unit Photos

- Christmas Menu

- Present Site of Camp

- Southwestern Bell Booklet

- Camp Wolters Souvenir Book

- IRTC Doughboy

- Soldier - Billy S. West

- Soldier Artist

- Soldier's Letters

- Soldier's Photos

- Fort Wolters

- United States Primary Helicopter/School

- Flight Training

- ORWAC Class 68-24

- WORWAC Class 67-5

- Training Aircraft

- Stagefields and Heliports

- Southern Airways of Texas

- USAPHS Commandants

- Battery D, 4th Missile BN 562nd Arty

- 328th U.S. Army Band

- Det. 20, 16th Weather Squadron

- Guide and Directory

- Crash Rescue Map

- Dave Rittman Photos

- Fort Wolters Photo Gallery

- Fort Wolters Ephemera

- Wolters Air Force Base

- Fort Wolters Main Gate

- Around Mineral Wells

- Texas Forts Trail

- Vietnam

- Sitemap

- Links

- About the Site

- What's New

It was many years ago, but I can still clearly remember pulling into the main gate at Fort Wolters, Texas, in late January 1968. Driving down Lee Road past the Post Headquarters, I pulled up to the Officer Student Company, which at that time was located in the 300 building area. There were already a few other new Student Officers hanging around the orderly room and I remember that we tentatively introduced ourselves and chatted briefly. That was my first introduction to some of my classmates, we were to spend the next eight months flying and learning together in what was perhaps the most interesting and exciting school available in the U.S. Army - the Officers Rotary Wing Aviator Course (ORWAC).

After signing-in and noting the time of the first scheduled formation we were released. Most Student Officers took the opportunity to head out towards Mineral Wells to locate some off-post housing. Several rented units at the Baker Hotel and a few were able to find apartments in Mineral Wells, Weatherford, or the outskirts of Fort Worth. Many of us found over-priced trailers to live in. Shattles Mobile Home Village and the Johnson Trailer Village were probably the two most popular trailer courts in Mineral Wells at that time.

After signing-in and noting the time of the first scheduled formation we were released. Most Student Officers took the opportunity to head out towards Mineral Wells to locate some off-post housing. Several rented units at the Baker Hotel and a few were able to find apartments in Mineral Wells, Weatherford, or the outskirts of Fort Worth. Many of us found over-priced trailers to live in. Shattles Mobile Home Village and the Johnson Trailer Village were probably the two most popular trailer courts in Mineral Wells at that time.

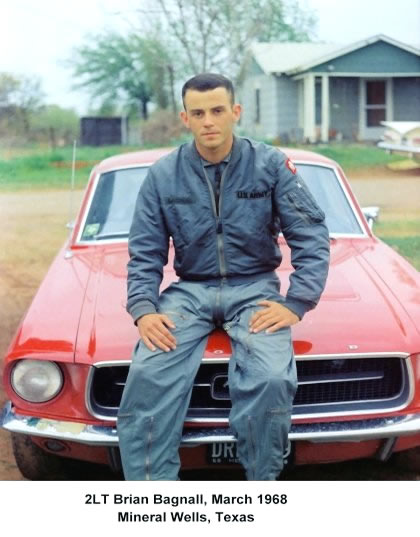

There were several vacant World War II barracks around the company area but they were not deemed to be suitable living quarters for the Student Officers. This pleased us to no end because it entitled us to receive a per diem rate of about $16/day. The average Student Officer starting Flight School in 1968 was a 2LT with less than two years service, which meant that in 1968 our monthly basic pay was $294.60/month, plus $47.88 for Subsistence and $85.20/month for quarters allowance (without dependent). While flying we also received Hazardous Duty pay of $110/month. There normally wasn’t much left after paying rent, our Officer’s Club bill, partying hard, and of course making the payment on the overpowered cars that we all seemed to drive.

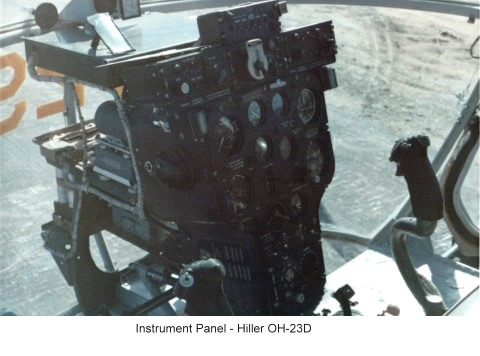

At our first formation on Feb. 5th, we were assigned to our flights and told that we collectively belonged to ORWAC Class 68-24 (“Brown Hats"). I personally was pleased to learn that I was assigned to Flight B-2, the only flight that would fly the Hiller OH-23’s. My trailer mate was assigned to fly the smaller Hughes TH-55’s and I was to warn him many times that if he was to let one “rip” in flight, the tiny “Mattel Messerschmitt” would almost certainly turn inverted.

Looking around me as we stood at parade rest I observed my fellow student pilots. On average they were about 20 - 22 years old and most had graduated within the previous year from Officer Candidate School (OCS). Perhaps 20% of the class were R.O.T.C. graduates and there were a sprinkling of Warrant Officers and usually at least one Captain in the class. Most everyone in our class who wasn’t a Lieutenant had already served a tour in Vietnam. The senior Officer in our class was an ex-Special Forces Captain who was made Student Class Commander by virtue of his rank. He was the first line of liaison and discipline between the Student Company Commander and the Student Officers. I don’t think he had to dispense much in the way of discipline but he was a very positive role model for all of us.

After a day or so for in-processing and picking up our flight gear we settled down into the routine of Flight School. We all merged together well and quickly good-natured verbal barbs, made generally along Branch lines, were zipping across the back of the buses as we headed out towards our first classes. The Infantry types certainly didn't look very bright, and honestly, the Armor boys looked somewhat scruffy compared to those fortunate enough to belong to the Artillery Branch (you know, Napoleon, President Truman, General Westmoreland, etc,). Those who were in the “non-combat” arms were quickly dismissed as either Truck Drivers (Transportation) or Latrine Diggers (Engineers).

During Flight School half of the day was spent flying and the other half at academics. The schedule alternated so that if you were flying mornings one week the next week you flew afternoons. The ORWAC classes did not have any pre-flight classes as such and we quickly started the process of trying to learn to hover and fly. We of course had already taken six months of leadership, military organization, tactics, etc. in OCS. Our paths frequently crossed with those of our Warrant Officer Candidate (WOC) counterparts. We saw them march in formation, and often saw them on the receiving side of the “constructive comments” made by their TAC Officers. I think that we almost universally sympathized with the WOCs - we realized that learning to fly was hard enough without the additional requirements of the living in the barracks and being subjected to the very rigorous military discipline that they had to comply with. Besides, we were virtually the same ages as the WOCs and only a short period of time separated us from when we were the under trodden at Fort Sill, Fort Benning, Fort Knox, and so forth.

The attrition rates for the ORWAC classes (10-15%) were less than the Warrant Officer Rotary Wing Aviator Course (WORWAC) classes(15-25%) because it was unusual for the Officers to get booted out for a non-Flight Deficiency reason. The myriad categories for which the SERB (Student Evaluation Review Board) at Fort Wolters would eliminate WOCs were only infrequently applied to the Student Officers. Those who suffered from “Lack of Character”, “Lack of Motivation”, “Lack of Aptitude”, etc., had usually been weeded out earlier at OCS.

Few Student Officers failed the Academic part of the course. The maintenance, aerodynamics, flying safety, navigation, weather training, and radio work classes were the same as the classes that the WOCs took. They were difficult, but not tremendously so. Not having a mandatory study hall like the WOCs meant that we had to impose a certain amount of self-discipline in the evenings. This of course was tempered by the fact that our evenings were our own and we cruised around, chased the local women, and generally had to contend with a series of distractions that usually kept us from seriously hitting the books.

We were however, almost always prepared for class and the Flight Line. If grades started dropping, the first step in re-focusing was always at the Student Company area where a verbal “boot up the backside” was generally enough to get the drifters back on course. Those who had trouble flying were either setback to the following (or next following) class or were eliminated and quickly sent to another duty station. Failing for Flight Deficiency reasons was not considered detrimental towards a future Army Career.

During Primary I our Academic and Flight Instructors were provided by Southern Airways of Texas. Among other things, they also under contract, provided the Bus Drivers, performed the maintenance on the training fleet, and ran the mess halls for the WOCs. The Academic Instructors included great many characters that could be counted upon to start every class with a ribald joke. The Flight Instructors included those who had learned to fly helicopters through a variety of means. Most were ex-military pilots who collectively had flown anything and everything including military aircraft in WWII or Korea. Others had learned to fly at their own expense and had moved to Mineral Wells as an opportunity to build hours in choppers. Overall, I think that the jobs that Southern Airways performed, and the people they employed were excellent.

My first Instructor was a fine gentleman named Mr. Popplewell. He was also a Warrant Officer in the National Guard, flying if I  remember correctly, out of Oklahoma. Mr. Popplewell flew smoothly, encouraged us often, and always had time to go over some of the finer points of airmanship with myself and the other two students he had in his group. There was however, one Instructor in the Flight who had a bad reputation as being a “screamer.” Mr. Popplewell couldn't fly one day and the “screamer” was detailed to instruct me. It was a windy, cold February afternoon when I jumped into the Hiller at one of the Stagefields. I struggled to control the chopper as we hovered across the field to the take-off panel. My five or six hours weren't quite enough experience for the level of proficiency this stupid man expected me to already possess. I had barely taken off when with a series of oaths he grabbed the controls, kicked the pedals and graphically showed me how much I was drifting off my ground-track. The rest of the instruction period seemed to drag on forever, positive reinforcement being totally absent from this man’s repertoire of training tricks. At the end of the instruction I felt much more appreciative of Mr. Popplewell and was extremely happy to see him back to work the following day.

remember correctly, out of Oklahoma. Mr. Popplewell flew smoothly, encouraged us often, and always had time to go over some of the finer points of airmanship with myself and the other two students he had in his group. There was however, one Instructor in the Flight who had a bad reputation as being a “screamer.” Mr. Popplewell couldn't fly one day and the “screamer” was detailed to instruct me. It was a windy, cold February afternoon when I jumped into the Hiller at one of the Stagefields. I struggled to control the chopper as we hovered across the field to the take-off panel. My five or six hours weren't quite enough experience for the level of proficiency this stupid man expected me to already possess. I had barely taken off when with a series of oaths he grabbed the controls, kicked the pedals and graphically showed me how much I was drifting off my ground-track. The rest of the instruction period seemed to drag on forever, positive reinforcement being totally absent from this man’s repertoire of training tricks. At the end of the instruction I felt much more appreciative of Mr. Popplewell and was extremely happy to see him back to work the following day.

Incidentally, the “screamer” got taught a good lesson a couple of weeks later. We were in the briefing room waiting for the Instructors to arrive. All of a sudden he came up behind us and yelled "ATTEN-SHUN”. We all jumped up to a rigid position of attention. I expected it was Colonel Huggins, the Post Commander, making an unexpected visit to the training area. Nope, it was the civilian screamer who started to berate us about our military deportment, attitudes and so forth. He only got through a couple of sentences when our Student Class Commander hollered “AT EASE” and invited the screamer to accompany him outside. We couldn’t hear what was being discussed but Student Class Commander seemed to be extremely angry as he made his points by jabbing his finger in the screamer’s chest. He never bothered anyone else again and our respect for the Student Class Commander grew even more. I was sorry that he hadn’t used his Special Forces training and kicked the jerk’s butt though!

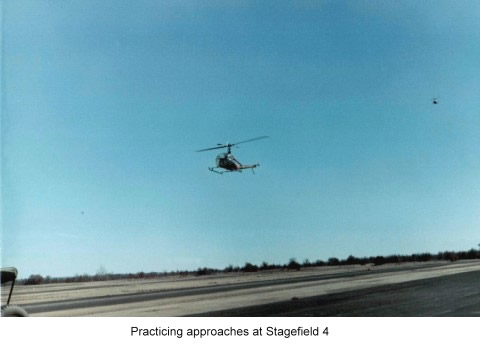

Initially flight training took place at the many Stagefields around Fort Wolters. Students took off from either the Main Heliport or from Downing Heliport and flew to the Stagefields assigned for that day’s training. Most Instructor Pilots (IP’s) had two or three students in their group. If you weren’t scheduled to fly with your IP to the Stagefield you took the bus with the other members of your flight. It was a good opportunity to get some sack-time, or to review your manuals and notes.

Stagefields had been purpose built and generally were designed along similar lines. On the edge of the Stagefield was a large tarmac area used to park the helicopters so they could be re-fueled, or to change students. A medium sized hut with tables was used by the Student Pilots to study while the others in their Instructor’s group were flying.

Stagefields had a small control tower adjoining the hut, from which the Flight Commander used to control the flying activities on the field. There were a total of six lanes at the Stagefields, aligned with the prevailing north-south winds in North Texas. These lanes, not surprisingly were designated lanes 1 through 6 outwards from the tower. Lanes 1,2,4 and 5 were used to practice take-offs and landings from either the east or west traffic patterns. Lanes 3 and 6 were for practicing autorotations.

Hovering practice would be obtained by moving between lanes and in the tarmac area. To teach emergency procedures and air work, the IP’s and Students frequently departed the Stagefields and flew in the nearby vicinity, or moved off to areas over the flat North Texas terrain that was less congested.

Hovering the aircraft was definitely difficult at first! Primarily an effort in coordination, it required both feet to control the pedals; your left arm moved the collective control up and down, while your right arm guided the cyclic control. Because the OH-23D was ungoverned, your left hand also controlled the throttle, attempting to maintain the engine rpm in a relatively narrow rpm range. While taking-off, hovering and landing the engine was operated at 3200 rpm. Normal flight required the engine to run at 3100 rpm.

If hovering was difficult at first, autorotations were both difficult and scary. They were initially practiced over Lanes 3 or 6, flying upwind at 500’ above ground level (agl). The practice autorotations were initiated by the IP rolling off the throttle and keeping it in the closed (override) position. This allowed the rotor to continue to rotate without engine power (“splitting the needles”). Collective pitch was reduced immediately and remained in the full down position unless it was necessary to prevent rotor over speed. Of course the helicopter descended like a ton of bricks towards the ground. At about 100 feet, the aircraft was flared using the cyclic to reduce apparent ground speed to a fast hover. At about 10 to 15 feet, collective pitch was applied to slow the rate of descent and assist deceleration. At between 1 to 3 feet collective was applied to cushion the touchdown while at the same time using the cyclic to place the helicopter in a skids-level attitude at touchdown.

We practiced autorotations incessantly, and it was due to our instructors thoroughness that many lives were saved in emergency situations. We were taught to constantly be aware of the wind direction as we flew away from the Stagefields. Smoke was a good indicator of wind direction; observing the water in the numerous small tanks (ponds) on the ground often showed the lee side and thus the wind direction. Failing these signs, some wise sage told me that most of the cattle parked with their butts to the wind. True or not, he made it sound believable and I for one spent too much time eye-balling the cattle on the grasslands below.

As we flew, we were frequently reminded to keep our heads always moving in a crosscheck inside and outside the cockpit. Airspeed….... Altitude…... rpm…... Ground track.… again….. Airspeed…... Altitude….. rpm….. Ground track. became our mantra. As soon as we started to relax, it seemed the IP would “split the needles” and we would have to initiate an autorotation. We would then dump the collective and turn the aircraft into the wind calling out when then rotor rpm was in the correct range: “Rotor rpm in the green.”

We also frequently practiced other emergencies such as tail rotor failures in flight; tail rotor failures during takeoff or hover; engine failures during flight, engine failures during takeoff or hover; engine fire during start; engine fire during hover. These plus many other situations were covered repeatedly and thoroughly.

The days moved quickly. On a blustery Friday afternoon I flew the last period with Mr. Popplewell. We talked as we hovered towards the parking area at the Stagefield. I wanted very much to solo that day but I was still slightly under the minimum of 10 hours of flight instruction that were required. I pleaded my case to Mr. Popplewell and he quietly acknowledged that he felt I was ready. I set the OH-23D down and he hopped out to talk to the Flight Commander in the Stagefield tower. A few minutes later he ducked under the turning blades and plugged in his helmet to the intercom. ‘Take her around for three circuits and pick me here afterwards ..... and good luck!”

The first thing that I thought about was the hope that I wouldn’t break anything - especially my neck. The bus taking the non-flying students waited at the end of the Stagefield and I could see my classmates cheering me on. Mr. Popplewell had done his job well, and although I was very stiff on the controls I managed to do what was required of me. I was ecstatic and the day was made even more memorable when Mr. Popplewell told me that the Flight Commander had stated that my solo efforts were among the best he had seen recently. True or not, I really appreciated Mr. Popplewell’s positive comments and professionalism.

After my three circuits, I picked up Mr. Popplewell and we headed south. We landed at the Main Heliport and after the debriefing headed back towards the Officer Student Company for release. This time however, the bus headed out towards the main gate and then turned west for the short drive towards the Mineral Wells Holiday Inn. My classmates grabbed me and heaved me into the swimming pool. The water in late February was pretty cold and I gasped as I went under. It took several attempts before my “friends” let me pull myself out of the pool. The dunking scene was to be repeated much more frequently as the rest of the class soloed with increasing frequency over the next couple of weeks.

After we were released on Fridays it was always mass bedlam as we departed quickly off-post. High-powered Mustangs, Firebirds, Corvettes, and motorcycles, left in a surge towards the main gate. While the married students relaxed around Mineral Wells or Possum Kingdom Recreation Center, the single students wandered further afield. The “Cellar” club was popular in Fort Worth and many drove over to Denton where it was easy to meet co-eds. American Airlines had their Stewardess Training Center by Greater Southwest Airport and some of the class started dating (and eventually) married Stewardess Trainees. I was lucky at Fort Wolters as my home was in Dallas about 80 miles to the east. All in all we enjoyed a very active social life on the weekends and generally enjoyed our stay at Fort Wolters immensely.

Periodically we had to fall-in for an inspection at the Officer Student Company area. A new commander once chewed us out royally for our appearance. We were berated several times for tickets that had been collectively received on post and from the surrounding areas. For a period of time motorcycle use was banned - partly due to road accidents and partly because of concern that when students had been asked to “join the needles and add power” during simulated engine failures, they had rapped on throttle in the wrong direction (i.e. the way their motorcycle throttles worked). Passing through 100 feet didn’t always allow the Flight Instructor enough time to take corrective action.

One of the Student Officers in another Class had been fairly beat-up when the nag he rented from the Boots and Saddle Club ran him into some tree limbs in the riding area on the east side of the Fort. We also lost a student who accidentally wounded himself in the foot in a weekend hunting accident. Besides these scrapes I remember that there were also a few flying fatalities at Wolters. These fatalities generally numbered between 6-12 a year and seemed to be clumped together. A Student Officer had crashed in a night cross country just before we started and it took several days before the wreckage was found on desolate ranchland by Newcastle, Texas. Considering that at this time there were in excess of 1,100 choppers flying out of Wolters, the fatality rate seemed very low.

The training at Wolters was divided into the Primary I and the Primary II phases. We were instructed in primary flying techniques which included pinnacle, confined area, slope operations, autorotations, emergency procedures, navigation at normal and low level (not below 500’) and night operations. Students received a total of about 110 flying hours during their stay at Wolters - 50 hours of dual instruction and 60 hours of solo flight. When we went through Flight School the Primary I phase (50 hours) was taught by Southern Airways, Inc., while the Primary II phase (60 hours) was conducted by Flight Departments “A” and “B” of USAPHS.

At periodic points during our flight training the Flight Evaluation Division evaluated us and it was necessary to pass the check ride before proceeding to the next phase. Our first night flights were certainly sobering experiences, particularly when undertaking night auto-rotations or when flying solo. Ground mists frequently sprang up during that time of the year and many times I wished that the US Army had thought it fit to equip the training fleet with artificial horizons for night flying.

We eventually completed Primary I - the gift bottles of whiskey that we gave our civilian instructors inadequately conveyed the gratitude we felt towards their efforts. Primary II was conducted from the facilities at Dempsey AHP, which was to the west of Mineral Wells near Palo Pinto. Here we met out military instructors for the first time and immediately started the more exciting advanced training activity. All of the instructors were Vietnam Veterans, divided into approximately 70% Warrant Officers and 30% Commissioned Officers.

The flying instruction was conducted in a relaxed but professional manner. Many of the single Warrant Officers chose to live in Fort Worth, which was about 45 miles to the east of Mineral Wells, because of the more active social life. The Flight Instructors often joked among themselves along the Real Live Officers (RLO’s) versus Warrant Officer lines. “Do you know how the Warrant Officer got his name? - he ‘warrant’ good enough to be an enlisted men and he ‘warrant’ smart enough to be an officer, so they called them Warrant Officer.” This frequently repeated comment made by the RLO’s usually resulted in several spirited rejoinders being made by the “Wobbly Twos”.

Rank on the flight line was usually forgotten, but the Student/Instructor relationship rarely was. Although the Instructors (particularly the Warrant Officers) were as wild as we were, we never socialized together after hours. I frequently had my butt vigorously chewed out by my Warrant Officer Instructor (CW2 Atkinson from Rhode Island) after a less than adequate period of instruction. The chewing-outs were all completely deserved, not so much for the way I flew, but more because I was becoming complacent and developing the “big-head” syndrome as my skills improved.

The long daytime cross-countries that we participated on were greatly enjoyed. On one of ours we flew up to Fort Sill which was about 150 miles trip over the various doglegs we followed. I had told several of my friends from OCS and the 3/38 Artillery when I was arriving. They all seemed appropriately envious at my newly acquired skills and I decided to give them a major thrill when I demonstrated an “airspeed over altitude” take-off when I departed. My effort can best be described as awful as I rocketed across the grass and converted too much speed into altitude. The OH-23 was normally pretty forgiving aircraft, but I am sure that I came close to introducing my main rotor blades to my tail-boom as I lurched into the sky.

We were all pretty competitive and vocal about our developing flying skills. During Flight School at Wolters we generally flew with two or three students to an Instructor. Occasionally you would fly with somebody besides your normal “stick buddies.” On one such occasion I was flying with another student for the first time on a night cross-country. He had a dry sense of humor and we needled each other incessantly as we tried to find Strawn, Mingus, Gordon and the other towns along our route.

As we returned to Dempsey we were both looking forward to de-briefing and then hitting the sack. He was flying and I looked over my shoulder as he turned from Base onto Final and increased the rpms from 3100 to 3200. A great big flame shot out the exhaust pipes, which scared the hell out of me. ‘Cripes” I exclaimed, ‘I think we are on fire!” My fellow student strained his neck and also saw the flames shooting out of the exhaust. Quickly, with a quavering voice he radioed in an in-flight emergency to Downing tower, which by now was only a couple of hundred yards away. Halfway through his call reality hit us both simultaneously - it was NORMAL for flames to be visible at night when you rapped on the throttle in the OH-23! He tried to cancel his declaration of the in-flight emergency but by now the Fire Trucks were rolling, and worst of all, most of our class had heard us make chumps of ourselves.

We were both razzed incessantly for quite a while but I escaped a lot of the heat by professing not to know why the “simpleton” flying declared the emergency. “Heck,” I told anyone who would listen, “any nitwit knows that the OH-23’s engine shoots out flame like that at night - I don’t know why he wet his pants and put out the call.”

Class 68-24 graduated at the Post Theatre on May 23, 1968, and while we knew how to fly we still had a long way towards becoming Army Aviators. Outside the theatre we said good-bye to those of our class who had been assigned to Hunter-Stewart for advanced helicopter training. Most of us were heading east towards Fort Rucker for advanced training. A few Student Officers, like myself, took the opportunity to get married en route. However the rest of training is another story....

Fort Rucker, Alabama.... Advanced phase of training....... the rest of the story

When we arrived at Fort Rucker we immediately had to scramble to find off-post housing. The Family Housing Office maintained a listing of available off-post rentals. If anything off-post housing was even more expensive and scarcer than at Wolters. Most of the class lived in trailer homes - mine was in a trailer court just outside the main gate in Daleville.

At Rucker we became ORWAC class 68-514 and we were divided into two sections. Our flight (B-2) from Wolters was kept together and were joined by several married WOCs from WORWAC class 68-513, who were allowed to live off-post at Fort Rucker. The other two ORWAC sections from Wolters were now combined for Flight Training and Academics.

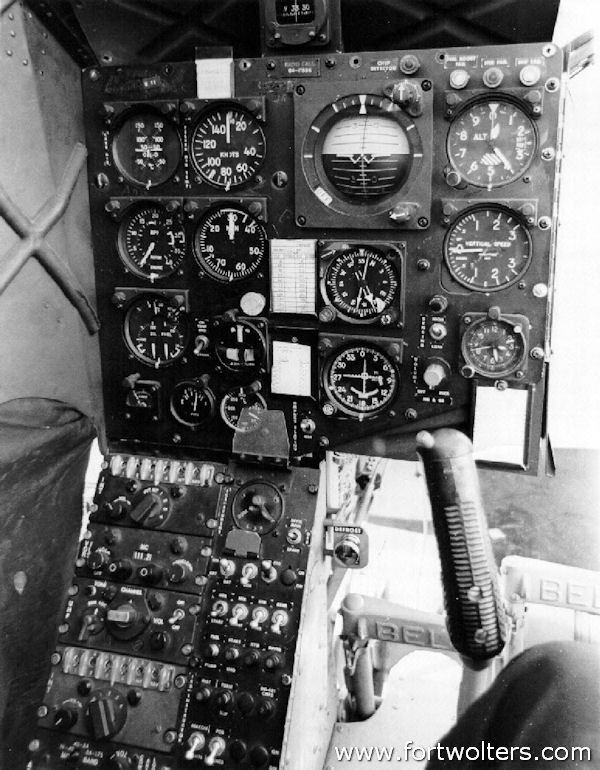

At Rucker the pace of training was rapid from the beginning. We were introduced to TH-l3Ts for Basic Instrument training. We flew out of Hanchey Heliport and had civilian instructors. This was my least favorite phase of flight school. To begin with, I never even got to hover the Bell TH-13T. I put on the hood over my helmet, extended the blind flying panels and waited for the Instructor to take-off. He would then hand-off the controls to me and we would fly to the training areas away from Rucker. An hour or so later, I would hand the controls back to him on short final and he would land it at Hanchey.

|

|

View of engine and transmission area of a Bell TH-13T used for instrument training at Fort Rucker. The U.S. Army purchased 411 of this two-seat instrument trainer which was powered by 270 hp Lycoming TVO-435-D1B piston engine. |

|

|

|

| Instrument panel from Bell TH-13T. |

Another reason I didn’t like Basic Instruments was the Instructor himself. He was a recently released ex-Army Captain with some very strange ideas about instructing. He sometimes would initiate political discussions in the air with me. Robert Kennedy had recently been assassinated and the Instructor expressed opinions that were much more liberal than you would expect from an ex-military man.

His greatest annoyance however, was to assign written assignments each night to myself and his other students. He would ask for a 250 word essay on “Descending Right Hand Turns” or, “Straight and Level Flight.” Then he would grade our efforts for punctuation and content - what a nerve! The rest of the class thought it was hilarious but these assignments took valuable time from our studies and preparation each night. We all repeatedly questioned him about the purpose of the assignments but got nowhere. Relations between us quickly cooled and all of his students got very low grades for the Basic Instruments phase of Flight School.

After Basic Instrument training we went to Shell AHP for Advanced Instrument training. This portion was taught by the military and I was really happy to get back to the open, no-bullshine atmosphere of Army Aviation. My Instructor was a CW2 from California who sported a great red moustache. He was really a free spirit and when I asked him what he did as a civilian he answered “surfed a lot.”

A couple of times he would allow me to nip over to Daleville and buzz my wife in the trailer. This was maybe three hundred yards from the main gate into Rucker and we would fly over the trailer at maybe 100’. “The secret is to get in and out quickly before anyone can read our tail number,” he would tell me with a big grin on his face. I also remember him fondly for a monumental drag race we got into when we spotted each other off-post one day.

As more and more of our class married, I found that we did more and more “married” things. To keep the wives busy and to prepare for them for the future roles as Army Wives, the Officer’s Wives’ Club sponsored a series of social activities. More and more we were night flying, or in the field during TAC X, and the get-togethers and trips made our wives less lonely while we were gone. My wife was 18 1/2 years old ( I was 21 years old) and it was her first time away from home. Such activities had an educational value and also resulted in greater understanding and support from our spouses. Staying home in the evenings had an additional benefit. I studied much harder and actually started moving upwards in the class standings.

Once a week it was “Bingo Night” at the Officers Club. Depending on our training schedule, we frequently attended as a class with our wives. We all sat together, and cheered wildly if anyone from our class won a prize. The prizes were the best I have ever seen for Bingo. One prize was a spanking new Cessna Cardinal (plus flight training). The amount of numbers that were called was raised each week until the prize was eventually won. Weekends were frequently spent on the beaches at Destin, Fort Walton Beach, or Panama City.

The next four weeks moved us to the Contact phase where we learned to fly the Huey (UH-l). Our first flight was memorable and I think we all fell in love with this wonderful aircraft. We flew out of both Knox AHP and Lowe AHP during the Contact phase. Slope landings, autorotations, confined area approaches were some of the many skills that we learned or refined during this period. My Instructor was a Captain who was out-processing for his next duty station in Korea. This meant that I flew with many different Instructors, as my assigned Instructor was frequently gone. This actually was a good thing as I felt I learned some good skills from many good aviators.

|

Part of the training fleet at Fort Rucker, 1968. |

There were many things that we knew had to be done prior to our approaching departure to Vietnam. One of them was to get our required shots before the end of Flight Training. One afternoon we had no flying training scheduled as we were night flying that evening. I took the opportunity to head over to the Hospital to get caught up on the required immunizations. I needed five or six shots but the Medical Orderly advised me not to receive more than three at a time. I really didn’t want to come back repeatedly and talked the Orderly into jabbing me with all of the needed shots then and there. That evening my left arm felt as if it had a canon-ball inserted under the skin. Every time I pulled collective my arm pained me greatly. My head ached and I generally felt awful. My performance was a very ropey effort that evening. Maybe the Orderly knew what he was talking about.

Contact went by in a blur and we next went into the tactics phase. Tactics was broken down into TAC 1 and then TAC X, both lasting 2 weeks. During TAC 1 we flew from Lowe AHP and were introduced to formation flying, sling loads, troop insertions and extractions, and night tactics.

I remember flying with a really “wigged-out” Warrant Officer during early formation training. We were flying trail formation and he kept on motioning me to fly closer, and closer, and ever closer to the Huey ahead. My blades seemed almost to overlap the other Huey’s blades and his tail-rotor danced just a few feet in front of our nose. Crud, I really couldn’t believe that we would have to fly this close tactically when we graduated Flight School.

Guess what, I was right. As we returned to base flying our “my nose up his butt” formation, the Flight Commander (a Major type) on the ground noticed us and screamed for us to back off immediately. The Instructor made a derogatory comment about the Major’s gonads to me over the intercom. When we landed the Major stormed over and immediately started a monumental chewing on the Warrant Officer. Incidentally, I have never ever flown that close to another aircraft since.

During TAC X we moved out to the field to simulate tactical conditions that we would encounter in Vietnam. If we weren’t night flying we were frequently entertained by some of our Classmates engaging in mammoth poker games. Stakes mounted quickly, I remember somebody who lost his motorcycle in a game. Another person was down about $2000 when the Flight Commander came in, shut down the game, and told everyone to return their winnings. Surprisingly nobody seemed to mind because the game had clearly gotten out of hand, and besides they were disturbing our precious sleep time.

|

TAC X - Maintaining a UH-1B. |

Towards the end of TAC X we had to return to the main post at Rucker for the “Escape and Evasion” (E&E) exercise. This was a training exercise which allowed the Student Pilots the opportunity to practice what had been taught them in the case they were ever forced down behind enemy lines. The one I had previously gone through at Fort Sill had been very realistic and very grueling. I certainly wasn’t going to get “captured” again (I was taking a snooze in a cave when caught) and get smacked around and humiliated in the “POW” camp.

Before we left for E&E we were briefed about the exercise. We would be divided into groups of about 4-6 students. Each group would be given a live chicken or a rabbit, an onion and a couple of potatoes. After being bused to the exercise area, we would have to build a lean-to shelter out of branches, etc. Then we would have to kill the chicken or rabbit, and prepare a meal using the carcass and the vegetables. All of us had to eat a fair portion of the meal as we received a grade for the shelter and the meal preparation.

After a pre-determined time the actual E&E exercise would begin with a Noise Device being detonated. The “aggressors” (enlisted men detailed to play the role of aggressors) would then do their best to capture us. Before we could complete the exercise successfully we first had to locate the ‘Partisan Point” in the thick woods. Once at the “Partisan Point” we would receive directions to the pick-up area where “friendlies” would be waiting and the exercise would be concluded.

We got on the buses and found the seven chickens to be virtually unmanageable. They were all over the place and we had a serious discussion about either ringing their necks on the bus, or heaving the noisier ones out of the windows. Not sure what the outcome of these two proposals would be on chances for passing the exercise, we finally found a more sensible solution. One of our classmates had read that chickens could easily be hypnotized. He took one of the chickens and laid its head down with its beak pointed down the grooves molded in the floor mats of the bus. Stroking its head gently he soon found it nodding off, completely hypnotized. A couple of minutes later he had all of the chickens fixed the same way. It was an amazing sight, seven chickens in a column, all perfectly still and oblivious to the bumpy back-roads over which we were traveling.

The chickens were still hypnotized when we arrived at the drop-off point for the exercise. Unfortunately for them they were quickly aroused when the bus stopped. I alone in my group had a knife, so I was delegated to dispatch the bird. This I did very clumsily by breaking its neck. I then cut off its head and held it by its legs to let the blood drain. For the rest of the exercise I stunk of a combination of chicken blood, wet feathers and my own sweat.

We cooked and then ate the bird which became a type of Chicken Stew. It was barely edible but I do remember one of our group asked for seconds. I was seriously wondering about his background when Aggressors were spotted moving towards us in the surrounding woods. This was before the Noise Device had been detonated, but the Aggressors obviously weren’t going to play fair - so away we ran. The next few hours were very difficult physically as the woods in that part of Alabama were very dense. I located the Partisan’s Point at about dusk and evaded the patrols before moving in to contact them. After looking over the directions and distance to the pick-up point, I made the decision to go east until I intercepted a range road. Choosing speed over safety, I then turned south and quickly moved down the shoulders of the road towards the pick-up point. Whenever I heard the frequent patrols or trucks coming down the road I froze until the danger had passed. It was about 1:00am when I finished the exercise - others were stumbling in over 12 hours later.

Our last major training exercise was to fly down the Elgin AFB in Florida and to extract some Rangers who were undergoing training there. After two solid weeks in the Florida boonies they were extremely happy to have finished their training. We stocked up with candy bars and passed them out to the grateful Rangers. They smelled pretty strong but nobody minded as we flew back in a vicious thunderstorm. I remember that at some times we couldn’t see much further than the nose of the Huey. On our maps we had marked and mentally noted a small tower on the East Side of the road when we flew in for the extraction. The tower was given a wide berth on the returning flight and when the storm lifted we pulled up to a higher altitude and bought the Rangers back in a fine fashion. 120 knots on the ASI, the blades making a mighty racket as they reverberated and banged through the air. What a great last training exercise to finish up flight school!

|

Flying a UH-1 Huey during the Contact phase - Fort Rucker 1968. |

I was, as it turned out, too happy too soon. Back at base we had one last action to take before graduation - the traditional class fly-by. We had watched some of the previous fly-bys and some looked good, and some looked not so good. Not many people wanted to be chosen for the formation and preferred to watch it from the ground as it passed over the reviewing stand in front of the Post headquarters. We chose names from a hat and I was one of the “lucky” group of about 100 Student Officers and WOCs who were to represent our class.

Fifty or so Hueys can churn up a bunch of air, particularly if you are towards the end of the formation as I was. I have to say though that after we pulled pitch and slid into our formation slots and thundered towards the reviewing stand that I was genuinely proud of how we looked from the air.

The air was very bumpy and as we moved from the “column of vees” formation into a trail formation prior to landing things started to get a little hairy. If the lead Hueys had sped up a little when the switch was called things might have gone a little easier. Instead the last Hueys suffered from a nasty concertina effect and many of us found ourselves standing on our tails, airspeed zeroed out, cursing mightily as we tried to slide into a trail formation prior to landing. Thank goodness that most of this took place after we had over flown the Post headquarters.

|

| Graduation Fly-by of classes 68-513 and 68-514, September 1968. There were about 50 Hueys participating. |

The next day we graduated with the ex-WOCs who had already been promoted to WO1s. Stepping across the stage to receive our wings was a very proud moment for all of us. My wife pinned the wings to my chest. Good-byes were said to the good friends we had made in Flight School, and then we all made a fast departure from Fort Rucker. We were going home to start our leaves prior to leaving for Vietnam.

Regrettably, most ORWAC classes haven’t really stayed close over the past 30 years. I envy the WORWAC classes with all their reunions but I realize that the main difference was that the WOCs lived together in close proximity for eight months. The Student Officers on the other hand lived separately, and enjoyed a much greater degree of freedom in our off-duty hours.

68-24 was representative of most of the ORWAC classes during the Vietnam era. While we haven’t had a reunion as a class since Flight School, I do often think of many of the great people I met there. Our lot as Officers was to lead, to fight, and to fly. The U.S. Army is a great organization because of the great people that were, and are, in it. Among the many that should be remembered by a grateful nation are the following members of ORWAC Class 68-24:

ORWAC 68-24 - Role of Honor |

||||

| Name | Home of Record | Date KIA | Province | Age |

| 1LT Stanley A. Brown | Albany, NY | 11/1/1969 | Tay Ninh | 23 |

| 1LT Daniel B. Cheney | Bellingham, WA | 01/01/1969 | Hua Nghia | 21 |

| 1LT Billy G. Creech | Chamblee, GA | 03/06/1969 | Thua Thien | 22 |

| 1LT Jimmy W. Crisp | Menard, TX | 06/05/1969 | Hua Nghia | 23 |

| CPT Charles B. Draut | St. Joseph, MO | 12/19/1969 | Binh Long | 22 |

| CPT Raymond R. Dulak | Corpus Christi, TX | 05/12/1970 | Pleiku | 26 |

| 1LT Thomas E. Jones | Beltsville, MD | 03/21/1969 | Hua Nghia | 25 |

| CPT Luther Lasater III | Garland, TX | 02/13/1972 | Ben Hoa | 24 |

| CPT James M. Lyon | Indianapolis, IN | 02/06/1970 | Thua Thien | 21 |

| 1LT Willard D. Richardson | Memphis, TN | 08/21/1969 | Thua Thien | 23 |

| CPT John P. Roe | Clinton, NY | 07/24/1969 | Kien Tuong | 27 |

| CPT Donald L. Swanson | Millbrae, CA | 01/31/1970 | Thua Tien | 26 |

| 1LT Deane A. Taylor Jr. | Atlanta, GA | 01/15/1969 | Quang Ngai | 22 |

| CPT Robert L. Wehunt | Lincolnton, NC | 12/23/1969 | Long Khanh | 22 |

“They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning:

We will remember them.”