- Home

- Camp Wolters

- A Model Soldier

- Camera Trip Through Camp Wolters

- Camp Wolters Longhorn

- Camp Wolters Ephemera

- Camp Wolters Guide

- Camp Wolters IRTC

- Camp Wolters Postcards

- Christmas Menu

- Present Site of Camp

- Southwestern Bell Booklet

- Camp Wolters Souvenir Book

- IRTC Doughboy

- Soldier - Billy S. West

- Soldier Artist

- Soldier's Letters

- Soldier's Photos

- Fort Wolters

- United States Primary Helicopter/School

- Flight Training

- ORWAC Class 68-24

- WORWAC Class 67-5

- Training Aircraft

- Stagefields and Heliports

- Southern Airways of Texas

- USAPHS Commandants

- Det. 20, 16th Weather Squadron

- Guide and Directory

- Crash Rescue Map

- Dave Rittman Photos

- Fort Wolters Photo Gallery

- Fort Wolters Ephemera

- Wolters Air Force Base

- Fort Wolters Main Gate

- Around Mineral Wells

- Texas Forts Trail

- Vietnam

- Sitemap

- Links

- About the Site

- What's New

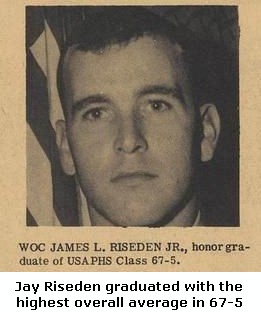

WORWAC 67-5 was chosen as "representative" of all the many classes that were trained at Fort Wolters from 1957 through 1973. Much changed in the 16 years that the United States Primary Helicopter School was in existence at Fort Wolters. The facilities, curriculum, training aircraft and methods of instruction all developed and evolved during this period. However, the "core" of the WOC training experience remained basically the same and I hope the following narrative brings back the essence of the training for all Warrant Officer Candidates in all For a comparison with the experience of a Student Officer going through the Officer Rotary Wing Aviator Class (ORWAC) training, click on the ORWAC 68-24 link. This historical website deals only with Fort Wolters and so this narrative is limited to WORWAC 67-5's time there. After graduation at Wolters many of the original class were assigned to other classes at Fort Rucker and the composition of 67-5 changed. My sincere thanks to Bart Kent, who generously made available his photos, class book, documents and other memorabilia of Class 67-5 for all to share. All of them were crucial for this narrative. Additional thanks to Bob Browne for sharing his photos and recollections of the "Green Hats." Further thanks to Jay Riseden for sharing his photos, memories and his artwork. Also thanks to Gary Cotton, brother of Mike Cotton who shared photos and memories of his brother, who was also my best friend. Photos and newspaper clippings of Class 67-5 can be also be viewed separately. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

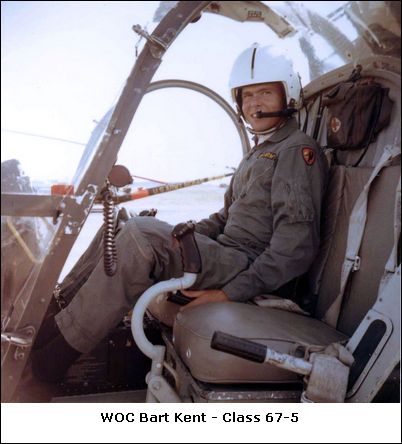

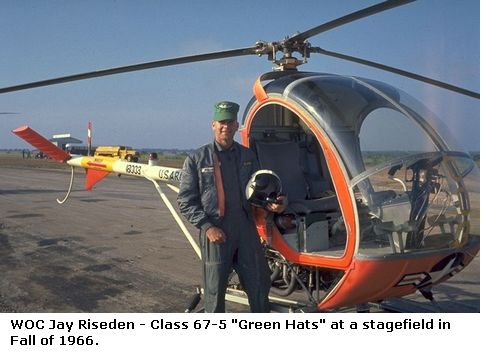

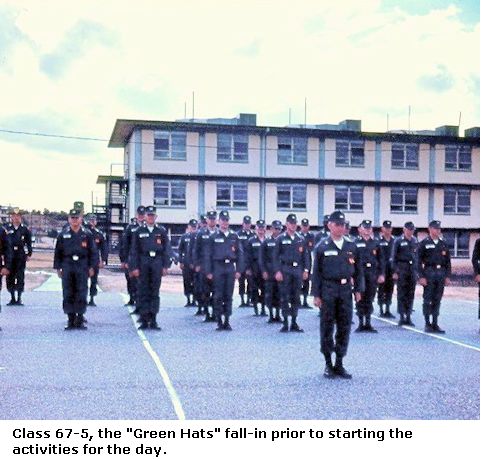

Flight School - WORWAC 67-5 The weather was a typically hot summer’s day for Mineral Wells, Texas, when Warrant Officer Rotary Wing Aviator Class (WORWAC) 67-5 started on August 6th, 1966. The 300 or so, Warrant Officer Candidates (WOC) were mainly right out of Basic Training, the majority from Fort Polk, Louisiana, but there were also many prior-service enlisted men who had also volunteered for the Army’s most exciting, and arguably, most difficult course of instruction. The prospect of learning to fly helicopters was exciting to all the new candidates. But before they would be allowed inside the cockpits of any of the 600 plus OH-23D and TH-55A helicopters in the training fleet at Fort Wolters, they would have to complete a four-week pre-flight training course. If successful, pre-flight would be followed by a sixteen-week course in primary and basic flight training at Fort Wolters, followed by a move to Fort Rucker, Alabama for a further 16 weeks of flight training. At the end of the total 36 weeks of training, the Candidates would receive their wings as Army Rotary Wing Aviators, be promoted to the grade of Warrant Officer (WO1), and finally, most probably receive orders assigning them to duty in the Republic of Vietnam. While in training the candidates who were E-4s and below would receive a temporary boost to an E-5 pay status which in 1966 was $200.40/month – but they did not receive any extra Hazardous Duty pay for being on flight status during training. At this time in 1966, pre-flight classes started every four weeks, and all candidates were assigned to the 5th Warrant Officer Candidate Company. Upon completion of pre-flight, students were assigned as a complete class to either the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th Warrant Officer Candidate Companies. Class 67-5, was to become the 2nd WOC Company, the “Green Hats” who were then commanded by Major Roy R. Steves. A “typical” WOC joining 67-5 was around 19-20 years old, and often had joined the Army to pre-empt being drafted. Undoubtedly bright, many shared the trait at that time, of being indifferent scholars and so had either left, or never attended college. All of them understood they had a duty to serve their country and had volunteered for what seemed to be an exciting prospect. The Army certainly provided the discipline to awaken incipient studying skills that allowed many in the class to later finish college and succeed in later professional careers. Army Regulation 601 – 108, covered the Warrant Officer Flight Training Option, and listed the following eligibility requirements:

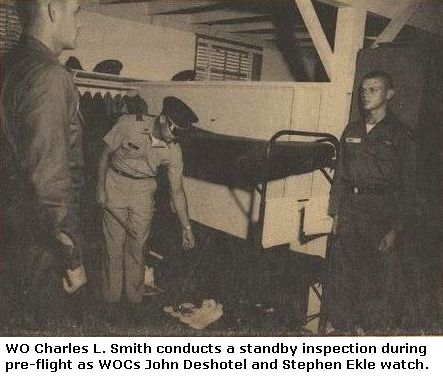

If the mental and medical prerequisites were met, be interviewed by, and approved by a Warrant Officer Flight Training Examining Board. Candidates arrived throughout the day, signing in at the 5th WOC Company Orderly room, which was located in Building 967. Duffle bags were unloaded, and the new candidates received a student packet containing the schedule and information necessary for in-processing. Glancing around, the new candidates saw that the 5th WOC area comprised of several WWII barracks, in good condition, which were designed to hold 62 troops each. Between the two rows of barracks were some small buildings that served various utility functions, such as the orderly room, company supply, mail-room and also the company day-room – to be used for off-duty recreational activities. Class 67-5 candidates quickly found that their time for enjoying any of the meager activities provided in the day room would be extremely limited in pre-flight. Also in the 5th WOC area was a Mess Hall, and a large open area that was used for Physical Training (PT). About this time a loud roar announced the arrival of a very agitated Warrant Officer. It was the candidates’ first introduction to Tactical Officers – group of very dedicated personnel who would work long hours and face the difficult task of melding the new candidates into knowledgeable student pilots. The Tactical Officers (TAC Officers) had all seen combat in Vietnam and now would interact on a daily basis with the candidates during their training at Fort Wolters. Among the duties of the TACs were to observe and evaluate assigned candidates during training, maintain candidate training records, prepare and present instruction in physical training, drills and ceremonies and techniques of inspection, conduct the Command Information program, supervise class social functions, and introduce all candidates to the expected standards of conduct. After Class 67-5 finished pre-flight they would be become the 2nd WOC Company and inherit a new cadre of TACs who would work with them for the last 12 weeks of flight training. Besides being agitated, the TAC appeared to be very annoyed at the demeanor of the new arrivals. A series of loud comments and commands were issued by the TAC - who appeared to have lungs of leather, and who quickly expressed his views about the appearance, ancestry and doubtful intelligence of the new arrivals. “Quit gawking around!” “Stand at attention” “What a pathetic lot of troops – the Army must be scraping the bottom of the barrel to send you duds to flight school!” The first TAC was joined by another TAC who appeared even more bad-tempered than the first one. Right in the faces of the small group of candidates he also started with a stream of invectives interrupted by a series of rhetorical questions delivered rapid fire which broke no logical answers. “What are you looking at Candidate – are you beady-eying me?” Apparently deciding that the candidates were indeed “beady-eyeing” him the new TAC invited them all to “drop and give me 50 push-ups!” Returning to the position of attention, the Candidates stood in the hot Texas sun in their sweat-stained khakis which by now had been reduced by the perspiration and heat to almost shapeless forms, almost devoid of any previous creases. Finally the candidates were dismissed to their assigned barracks, lugging their duffle bags at the double-time to their new homes. There they found other new candidates and after grabbing one of the still available bunks started to unpack and make up their bunks. They found they had all been assigned to a specific Flight, generally by last-name in an alphabetical sequence (ex. Flight A-1, A-2…B1, B2...etc). Introductions were quickly made and any gained knowledge collectively shared. Already the often repeated mantra of “cooperate and graduate” was in evidence and the new candidates started to gel as a cohesive unit who were all trying to accomplish the same goals.

The first couple of days of pre-flight were taken up with basic administrative matters: personnel records were turned in, payroll matters resolved, vehicles, firearms and pets were registered, dependent privilege cards obtained for the student’s wives, and an initial text book issue received and signed for. Classes started quickly and covered a variety of flight related topics as well as other subjects important in their development as future Warrant Officers. Perhaps the most difficult class taken in pre-flight was map reading. Many candidates just couldn't understand the material and many extra hours were spent in extra studies. Those candidates who quickly grasped the theory and application of the map reading concepts were generous in helping their classmates. Each week a weekly schedule was published for student information describing the specific instruction to be presented during each weekly period – it contained the following information:

Each candidate was required to read the company bulletin board at least twice daily, once prior to 2300 hours. Excuses for being unaware of a required formation, activity or class simply were not accepted. Warrant Officer Candidates were also expected to comply with the tenets of an Honor Code and Honor system designed to reveal those who were incapable of measuring up to proper Warrant Officer standards and to eliminate the untrustworthy. The code, which was similar to the honor codes instituted at Officer Candidate School (O.C.S.) and West Point was succinctly stated in the following basic points:

Finally, the Honor Code was administered by the Honor Committee elected by the Warrant Officer Candidates. The pressure on the members of Class 67-5 was unrelenting and soon some of the candidates found they were unable or unwilling to achieve the high standards necessary to continue in training. They either resigned or were referred to the Student Evaluation Review Board (SERB) and setback to a following class or eliminated completely from training. The process was quick and empty bunks in the barracks attested to their departure. The former candidates were moved to the Casual Company pending re-assignment by the Army. Being young and resilient, as well as having just completed Basic Training, most candidates acclimated to the harsh Texas weather where the temperatures frequently exceeded 100°F. PT training was held frequently in the area to the east of the barracks. The grass was almost non-existent there and what remained had been frazzled and burned by the merciless sun. Huge ants were in evidence and care had to be taken where the WOCs lay down before performing the various PT drills. Salt tablets were available from dispensers located near the water fountains in the barracks and their consumption was highly recommended. There were days however where even the Army decided it was too hot for PT exercise and such training was cancelled. These days were designated “black flag” days because of the small black flags that were run up the flagpoles to provide a visual notification. The four weeks of pre-flight had rolled by quickly and the TAC officers had done a thorough job of training and indoctrinating class 67-5 for the remainder of their training cycle. Prior to the end of the 4th week, each candidate received two flight suits, a MA-1 flight jacket and a shiny white APH-5A flight helmet. There was a buzz of excitement among the candidates – the flight gear indicated that flight training was just a few days away. Then finally, the big day arrived and 67-5 moved “up the hill” from the Pre-Flight area with its old WWII wooden barracks, to newer barracks located about a mile to east where the WOC billeting area was situated.

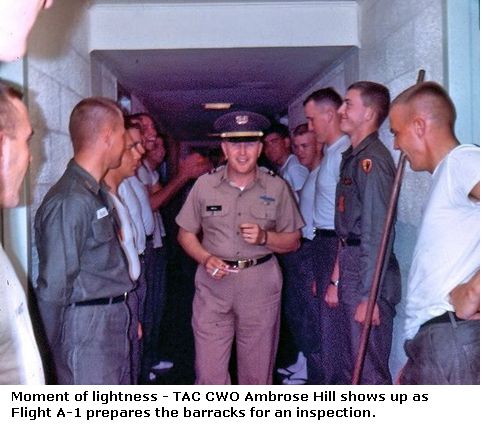

The 2nd WOC Company at that time was ably commanded by Major Roy R. Steves, an Army Aviator in the Field Artillery Branch. The TAC staff serving under Major Steves included CW2 George Marcotte, CW2 William Terry, CW2 C.W. Parker, and CW3 Ambrose Hill. All of the cadre of the 2nd WOC Company were Vietnam veterans and all highly dedicated. The hours they worked were long, their standards high, and the discipline and “constructive criticism” they liberally distributed was dispensed in a manner that was at least consistent. As the candidates progressed through training more privileges, including passes, became available and as long as the standards of the Warrant Officer Candidate Student Guide were followed, candidates could stay on the periphery of their TAC's all-seeing eyes and hopefully remaining out of their cross-hairs. Class 67-5 was divided into seven different flights, candidates in each flight roomed in close proximity and attended all In 1966, when Class 67-5 was in training, most of the Flight Instructors and Academic Instructors in the Primary Phase worked for Southern Airways of Texas. Besides the war in Vietnam, a very real Cold War meant that the Army had an ever increasing need for Rotary Wing Aviators. There just were not enough trained Aviators available to meet the Army’s needs and also provide additional capacity to train and support the flood of new student pilots. Southern Airways was a civilian firm that had held a contract with the Army to provide certain tasks in connection with the operations at the U.S. Army Primary Helicopter School since 1956. Besides Flight and Academic Instruction, Southern Airways also performed maintenance on the training fleet, ran the Mess Halls for the candidates, and also provided the Bus Drivers who ensured the students were all delivered, on-time where they needed to be. Military Officers provided academic instruction in military matters and also the flight instruction in the Advanced Phase. Finally the big day arrived – the reason why everyone had signed up for Flight School. The buses met the WOCs and drove them out to briefing rooms located across Grant Road from the Main Heliport. There they were introduced to their new Flight Commander and assigned to their new Instructor Pilots (IP). Each IP was responsible for around three or so student pilots – the group known as a “stick.” It was well known how important it was to have the correct Student-IP relationship. Many good pilots just weren’t able to be become good instructors, and couldn’t impart the vital lessons of airmanship to the tyro pilots. That said, Southern Airways had a rigorous training program and the great majority of their IP’s were very competent and followed the prescribed flight training syllabus closely. When class 67-5 attended Fort Wolters in 1966, flight training was broken down into three stages: Pre-Solo, Primary and Advanced. The scheduled flight time for the various stages was: Pre-Solo 17:00 flying hours Primary 33:00 flying hours Advanced 60:00 flying hours The hours were the maximum time allocated and it was expected that less time would be required by the average students. One of the students from the stick was chosen to fly with the IP for the first period, and the remainder left the briefing rooms, and were bused to the assigned stagefield with the admonition to study their training material. There they waited in the ready room until they were summoned for their turn at flying. Facilities at the different stagefields varied, but there was generally always a re-fueling truck, as well as a Southern Airways mechanic available. The ready room had a few tables with chairs, air conditioning (sometimes), potable water, latrines (permanent or not), a blackboard and a large area map. The Flight Commander controlled flying from a small tower or small hut nearby. The flight instruction Class 67-5 was one of the earliest classes that did not have to perform solo autorotations. Dropping quickly from the sky, what looked like a bad situation was controlled by the IP’s with a smooth flair, leveling and then a cushioning control to land gently on the ground. Most of students in 67-5 were glad that they weren’t initially expected to do such maneuvers by themselves, but as their flying hours mounted they performed this vital maneuver dozens of times. In fact, in their future careers as Army Aviators, real life autorotations were often safely performed and the thoroughness of their instruction at Fort Wolters was validated and seen in lives and aircraft saved. Flying every day, proficiency increased and the new student pilots soon found they could hover the trainers and perform the basic flight maneuvers in a safe manner. Proficiency would come with experience, but after at least ten hours of dual instruction the IP’s deemed that their charges were ready to fly solo. On the appropriate day, the IP gave some last minute instructions, stepped out of the aircraft, and watch the soloing students perform three take-offs and landings at the stagefield. This momentous occasion was later celebrated by the new pilots being thrown into the Holiday Inn swimming pool in Mineral Wells or a handy drainage ditch. The “solo wings” that were sewn onto the green colored caps attested to the importance of this achievement and it was with pride that the visual symbol of proficiency was worn.

By early October all of 67-5 that had successfully soloed continued to progress and continued with solo flights and eventually were allowed to fly with other students. They were introduced to day cross-country flights where their map reading skills were put to use. Night flying was scheduled, first dual with the IP’s, and then solo. The first night autorotations were performed and definitely gave student pilots pause to think - the ground came up quickly and the diminished visibility made a difficult maneuver even more difficult. Besides performing well enough daily to satisfy their IP’s, and receiving a good grade slip, there were Flight Check-rides (checks) that had to be passed at different stages: A Pre-Solo check was given as directed by the Flight Commander.

Flight instruction was demanding and exciting, but also rewarding and fun. Day cross-country flights were looked forward to and local civilian airports – Stephenville, Breckenridge, Abilene, Eastland, among them were visited. Night cross-country flights were undertaken in the Advance Stage and sometimes when lost, climbing to higher altitude would allow the students to find their positions by locating the lights of the Baker Hotel in Mineral Wells. Similarly, the string of lights that showed the towns of Strawn, Mingus and Gordan in a line to the south, saved many of the students from getting lost, and subsequently being “ribbed” by their classmates. The flying was fun but periodic accidents, often fatal, would reinforce that fact that flying helicopters, in combat or not, was still a very dangerous occupation. In August, 1966, just after 67-5 had started Pre-Flight a student pilot in a preceding class had died when his TH-55A had crashed near Mineral Wells. The subsequent investigation showed he had lost control while attempting to change seats in-flight. His youthful mistake caused tragic results and made everyone to shake their heads and wonder why. On October 10th, 1966, a Student Officer and his Instructor Pilot were killed in an accident near Graford. This was followed by another double fatality on November 29th, 1966, involving a WOC from another class and his Instructor Pilot who crashed 3 miles to the southwest of Mineral Wells. Then on December 5th, 1966, just two weeks before graduation, the 2nd WOC was devastated when it was learned that WOC James R. Carlson had been killed in a mid-air collision about 10 miles to the northwest of Mineral Wells. The other student involved survived and was able to provide some details of the accident but it just appeared to be an unfortunate occurrence. WOC Carlson was assigned to Flight A-2 of the 2nd WOC and was a popular candidate who was doing well in training. He was the first on many 67-5 students who later lost their lives in the service of their country. Along with learning to fly, the students in class 67-5 also had to maintain a passing average of at least 70% in all of their Academics. A total of 1000 points could be attained in both the Pre-Flight and Primary phases, broken down as follows: Pre-flight:

Primary - Academics:

Primary – Flight:

A study hall for 1½ hours on Sunday through Thursday evenings was mandatory for all WOC’s from the 1st through the 16th week of training. The study hall policy was a little more lenient during the 17th through 20th week of training for those Candidates with an average of 80% or higher – they were exempt if their flight grades were not declining and all tests were passed. The barracks were quiet during study hall and the enforced period of study soon uncovered nascent study skills. An average of 70% was required to successfully complete each phase of training. All students with an academic average of 75% or less were placed automatically on probation and subject to mandatory study halls and possible pass restriction. Most students found the academics to be tough but not totally brutal. If students were unable to maintain a 70% average they were referred to the Student Evaluation Review Board and could be set-back; retained in the current class; or eliminated. All eliminated students were quickly removed from the WOC Company and transferred to the Casual Company pending further orders. As most of the WOC’s were just out of Basic Training with limited skills, elimination often meant a brief period of Additional Individual Training (AIT), and dependent on the Army’s needs, was often followed by assignment to Vietnam. Along with the rigorous flight and academic requirements, WOC’s were also required to learn military organization and leadership. Using similar time honored procedures from Officer Candidate Schools (OCS), a Battalion Staff was established by selecting outstanding candidates from each section of the Senior Company. This Battalion staff was composed of the following positions, similar in nature to a Battalion staff of regular line units:

Additionally, Student command position assignments were established in each WOC Company. The company chain of command could be changed as necessary, but did not exceed a period of one week. The student chain of command for each company was structured as follows:

Each of the leadership positions wore insignia of rank to designate their leadership status and after their tour of duty was complete they were responsible for rating their subordinates and for submitting after-action reports. Most of the WOCS in 67-5 were young and had not held leadership positions in the military before, and seeing their names posted on the barracks bulletin board for the more responsible positions certainly invoked feelings of trepidation and concern. As the training progressed and confidence grew, concern lessened and performance in these positions became “old hat.” A demerit system existed for all WOCs that determined whether the candidates would be able to receive pass privileges. Technically, it was a merit and demerit system, but as most WOCs soon realized there were many opportunities to receive demerits but only seldom were these offset by the award of a meaningful number of merits. The number of merits and demerits received were accumulated and carried through the entire course and were considered in the candidate’s military aptitude evaluation.

Merits were issued for good checks rides (90 and up) as well as academic grades (90 and up), as well as special awards by the Company Commander. TACs would sometimes award merits for the same things they observed positively (ex. “MD – Displays” or “MJ – Personal Appearance”). So, even though fewer demerits were allowed as training progressed, in actuality fewer demerits were received as candidates adapted and became more compliant with the system. The end result was that candidates were better able to prioritize, worked more efficiently, cooperated better with their classmates and so were able to enjoy more daily and weekend passes.

Fort Wolters had many activities that the WOCs could enjoy in their free time and those so inclined and talented enough were able to participate in the WOC choir and various intramural sports. In fact, 67-5 had a quite successful basketball team and was often able to display their dominance over the other WOC companies in the fall of 1966 season. While free time was always limited for the “Green Hats” of class 67-5, time also had to be set aside for personal business and errands. The post shuttle bus ran on a frequent schedule Monday through Friday from 7:00 am - 4:30 pm and transported candidates all around the post. Located nearby to the WOC area was a PX annex, Service Club annex, Student Mail Room, and the Book Store. A Barber Shop in the student area provided the required haircuts for 70 cents each visit, and there was also a location where uniforms could be cleaned, tailored, and insignia sewn-on. The WOCs by virtue of their temporary E-5 pay grades were able to join, and use the facilities of the N.C.O. club - whose dues were an affordable $1.00 per month. If the WOCs were over 21 years old, membership in the NCO club also allowed them to purchase alcoholic beverages in the Post Package store. Of course, the Package Store was off limits to those under 21 years of age and on-post those under-aged WOCs could only drink beer with an alcoholic content of 3.2% or less.

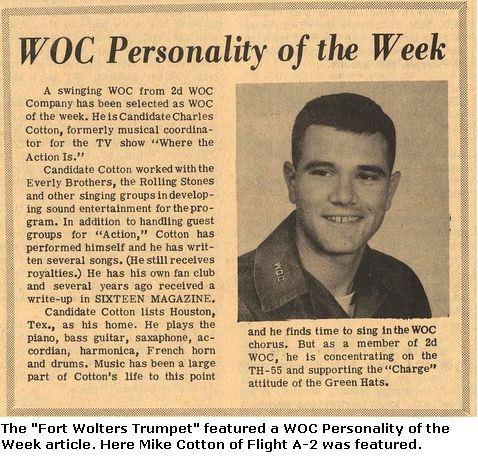

The candidates of 67-5 actually were developing a lot of swagger as the training progressed. Each flight had their own guidon and competed in a friendly way with each other and with the other WOC companies. The “Green Hats” felt they looked smarter, marched better, and in general were just a notch above the other WOC Companies. Real or imagined, the TAC Officers had encouraged their show of spirit and pushed their charges in a way that encouraged the development of unit cohesiveness and esprit de corps that would be so important in their future careers in combat situations. Besides the regular Student Change of Command Formations, the WOC companies periodically had to march in post-wide parades on the main parade ground adjacent to Beach Army Hospital. There was usually at least one practice before the actual ceremony and all of the WOC companies had to march the mile plus distance to and from the parade ground. Before setting off, an inspection in the company area ensured that all the candidates were resplendent in their greens, with brass shining and low quarter shoes polished to a high gleam. One parade was to be different however; some of the class had decided that a pair of low quarters would be left on the parade ground, ostensibly to cause puzzlement when they were later discovered. The planning and execution of this lark was carried out to perfection and the bold volunteer was able to deposit the shoes and return undiscovered to the company area afterwards. It was probably a tractor driver cutting the grass who later discovered the shoes and hopefully was able to make good use of the donated footwear. Training moved along, check-rides were completed, academic tests passed, and military and leadership knowledge gained. When class 67-5 completed the 16th week of training they became Senior Candidates, and wore the orange tab with black stripe that designated this status on their uniforms proudly. As training wound down, planning began for the traditional graduation party. A band had to be found and engaged to provide music at the party and this initially posed a problem. However, Candidate Mike Cotton had previously fronted a successful rock-band in south Texas, and was able to contact his brother Gary who appeared with the band to provide the live music. Dates were invited, libations flowed freely and a good time was had by all at the Baker Hotel in Mineral Wells.

Out processing had already been finished; manuals and equipment turned in, and personnel and pay records collected. Good-byes were brief and most of the candidates quickly departed for Fort Rucker and advanced flight training and the opportunity to fly the UH-1 Huey. Some of the class opted to say at Fort Wolters for four weeks and a brief leave over the Christmas Vacation and so actually graduated from Fort Rucker with WORWAC 67-7. Fort Wolters had trained all of the WOCs of 67-5 well in the primary phase – they had all flown solo so they were in fact pilots. Fort Rucker would add further training and polish their skills so that in a further 16 weeks they would be awarded their wings as Army Aviators. Nearly all of the class would then receive their orders to the Republic of Vietnam. Lifetime friendships had been formed and there have been many opportunities for the “Green Hats” of 67-5 to reunite and reminisce in the future. WORWAC 67-5 was representative of most of the classes during the Vietnam era. Most of the young men who started Flight School on that hot summer’s day in 1966 have long matured, started careers and families. Many had their lives cut short in the service of our great country. The following members of class 67-5 who graduated from Fort Wolters are remembered by a grateful nation and with fondness by their classmates:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The designated time for the next meal had arrived and the candidates double-timed over to the mess hall in small groups. The next day, by which time most of the new candidates had arrived, saw them march to the mess hall and stand at parade rest in the line waiting to enter the dining area. A Squad Leader was stationed at the door to maintain an orderly flow of candidates entering and leaving at one time. During pre-flight candidates had to remain standing at a table until all occupants at that table were present before sitting down for their meal. Candidates could not indulge in excessive or loud conversation during the meal, and when finished could leave individually upon excusing themselves from the table. The WOCs found the mess hall clean and the meals well prepared – in fact the standards were much better than the typical Army mess halls. All cooking and food preparation was contracted to Southern Airways of Texas and the candidates did not have to stand Kitchen Police (KP) duties during training.

The designated time for the next meal had arrived and the candidates double-timed over to the mess hall in small groups. The next day, by which time most of the new candidates had arrived, saw them march to the mess hall and stand at parade rest in the line waiting to enter the dining area. A Squad Leader was stationed at the door to maintain an orderly flow of candidates entering and leaving at one time. During pre-flight candidates had to remain standing at a table until all occupants at that table were present before sitting down for their meal. Candidates could not indulge in excessive or loud conversation during the meal, and when finished could leave individually upon excusing themselves from the table. The WOCs found the mess hall clean and the meals well prepared – in fact the standards were much better than the typical Army mess halls. All cooking and food preparation was contracted to Southern Airways of Texas and the candidates did not have to stand Kitchen Police (KP) duties during training.  Building 756 was the new “home” for class 67-5. It was a three story cinder-block building that had been built in 1953. Much more substantial than the WWII barracks still in use throughout the Army, the barrack was not air-conditioned, nor did it have the old “swamp coolers” that were used in pre-flight barracks. Substantial windows opened upwards in each room to provide some relief, and often the end-doors at the end of the hallways were opened for cross ventilation. Located on each floor in the middle of the barracks were the sinks and latrines which were to be cleaned each morning before training began and the TACs could begin their daily inspections.

Building 756 was the new “home” for class 67-5. It was a three story cinder-block building that had been built in 1953. Much more substantial than the WWII barracks still in use throughout the Army, the barrack was not air-conditioned, nor did it have the old “swamp coolers” that were used in pre-flight barracks. Substantial windows opened upwards in each room to provide some relief, and often the end-doors at the end of the hallways were opened for cross ventilation. Located on each floor in the middle of the barracks were the sinks and latrines which were to be cleaned each morning before training began and the TACs could begin their daily inspections. classes together. Initially each flight started with about 40 – 45 students who were generally assigned by alphabetical order, which was altered somewhat as the class received “set-backs” from other classes. Each flight was trained on just one type of training helicopter while at Fort Wolters. Flights A1, A2, A3, B1 and B2 flew the

classes together. Initially each flight started with about 40 – 45 students who were generally assigned by alphabetical order, which was altered somewhat as the class received “set-backs” from other classes. Each flight was trained on just one type of training helicopter while at Fort Wolters. Flights A1, A2, A3, B1 and B2 flew the  for everyone always started with an introduction to the art of hovering. The IP let the students learn to use the helicopter’s pedals first as he managed the collective and cyclic controls. Next the students were allowed to use the collective control and then finally the cyclic control. As the students tried to absorb the instruction and put into practice what the IP was saying, they could see other helicopters gyrating widely in the practice area. The same was happening in each cockpit and the IP’s, who seemed somewhat nervous and “twitchy” had to frequently re-exert control with a curt, “I’ve got it.” The wild gyrations were stopped quickly and the process started again and again. Both the students, and certainly the IP’s, were glad when the hovering practice ended and other airmanship topics were started: take-offs, landings, turns, straight and level flight and of course the dreaded autorotations.

for everyone always started with an introduction to the art of hovering. The IP let the students learn to use the helicopter’s pedals first as he managed the collective and cyclic controls. Next the students were allowed to use the collective control and then finally the cyclic control. As the students tried to absorb the instruction and put into practice what the IP was saying, they could see other helicopters gyrating widely in the practice area. The same was happening in each cockpit and the IP’s, who seemed somewhat nervous and “twitchy” had to frequently re-exert control with a curt, “I’ve got it.” The wild gyrations were stopped quickly and the process started again and again. Both the students, and certainly the IP’s, were glad when the hovering practice ended and other airmanship topics were started: take-offs, landings, turns, straight and level flight and of course the dreaded autorotations. While ten hours of dual instruction was usually the minimum hours needed to solo, some students didn’t learn as quickly and it was usually at around 13 – 14 hours of instruction that most soloed. The Pre-Solo phase was scheduled for a total of 17 hours, but some students weren’t doing well and if appropriate they received a mandatory progress check conducted by the Military Flight Evaluation Division. If they performed satisfactorily they were allowed to solo and continue with the class; if they failed they were referred to the Student Evaluation Review Board where they were usually eliminated for “Flight Deficiency,” or if lucky, set back to a following class for additional instruction. Being a “late bloomer” and soloing late was not an indication of a lack of flying ability, and indeed proficiency and ability was quickly gained once the “light was turned on.”

While ten hours of dual instruction was usually the minimum hours needed to solo, some students didn’t learn as quickly and it was usually at around 13 – 14 hours of instruction that most soloed. The Pre-Solo phase was scheduled for a total of 17 hours, but some students weren’t doing well and if appropriate they received a mandatory progress check conducted by the Military Flight Evaluation Division. If they performed satisfactorily they were allowed to solo and continue with the class; if they failed they were referred to the Student Evaluation Review Board where they were usually eliminated for “Flight Deficiency,” or if lucky, set back to a following class for additional instruction. Being a “late bloomer” and soloing late was not an indication of a lack of flying ability, and indeed proficiency and ability was quickly gained once the “light was turned on.”  Company Headquarters:

Company Headquarters: Much of the WOCs appearance, deportment and behavior was subject to running afoul of the demerit system. Demerits were most commonly awarded by the TACs during their daily inspection of the barracks. by The Student Guide contained all the rules, illustrated with many diagrams of how the barrack rooms and individual displays were to be presented. The rooms, common areas, wall lockers and clothing displays that were left with meticulous precision when the candidates left for morning classes would be found to be sadly lacking by the eagle-eyed TACs. Merits and demerits were initially recorded on the Report of Merits and Demerits form left on the table in each room. Usually marked by the inspecting TACs with the discrepancy code (ex. “E6” - Boots not shined; “FF3” - Uniforms not evenly spaced; or “Y8” – Dirty Razor), candidates were often instructed to add discrepancies to the list (i.e., needs haircut) by the TACs and at the and of each day, the demerits were totaled and the form initialed.

Much of the WOCs appearance, deportment and behavior was subject to running afoul of the demerit system. Demerits were most commonly awarded by the TACs during their daily inspection of the barracks. by The Student Guide contained all the rules, illustrated with many diagrams of how the barrack rooms and individual displays were to be presented. The rooms, common areas, wall lockers and clothing displays that were left with meticulous precision when the candidates left for morning classes would be found to be sadly lacking by the eagle-eyed TACs. Merits and demerits were initially recorded on the Report of Merits and Demerits form left on the table in each room. Usually marked by the inspecting TACs with the discrepancy code (ex. “E6” - Boots not shined; “FF3” - Uniforms not evenly spaced; or “Y8” – Dirty Razor), candidates were often instructed to add discrepancies to the list (i.e., needs haircut) by the TACs and at the and of each day, the demerits were totaled and the form initialed.  As the training progressed, and depending on the number of demerits that had been accumulated, WOCs took advantage of their earned off-post passes, These were of differing lengths of time – the longest running from Saturday at 1:00 pm to Sunday at 5:00 pm. Candidates were able to wear civilian clothing after pre-flight training, and as several WOCs had brought their private vehicles to Fort Wolters, on weekends there was a exodus of cars heading to the local environs in search of female companionship. Weatherford College, North Texas University at Denton, Arlington State College at Arlington, and the American Airlines Stewardess Training Center were popular places to meet and date the pretty co-eds. Of course many choose to spend time in other pursuits, but most WOCs realized that their off-duty behavior was always subject to scrutiny and depending on the infraction, could sometimes lead to being bounced out of flight training.

As the training progressed, and depending on the number of demerits that had been accumulated, WOCs took advantage of their earned off-post passes, These were of differing lengths of time – the longest running from Saturday at 1:00 pm to Sunday at 5:00 pm. Candidates were able to wear civilian clothing after pre-flight training, and as several WOCs had brought their private vehicles to Fort Wolters, on weekends there was a exodus of cars heading to the local environs in search of female companionship. Weatherford College, North Texas University at Denton, Arlington State College at Arlington, and the American Airlines Stewardess Training Center were popular places to meet and date the pretty co-eds. Of course many choose to spend time in other pursuits, but most WOCs realized that their off-duty behavior was always subject to scrutiny and depending on the infraction, could sometimes lead to being bounced out of flight training. The “Fort Wolters Trumpet” was the weekly newspaper that allowed WOCs to learn of what was going on outside of their somewhat sequestered world. Charles “Chico” Alvarez and other WOCs volunteered to collect and contribute news and articles of interest about 67-5 for the “Trumpet.” The weekly column about the class had a firm deadline and everything written had to be vetted by Company cadre before it was submitted for publication. Seeing one’s name, or indeed anything positive in print about the “Green Hats” provided a valuable boost in morale and esprit de corps and helped compensate the writers for the valuable personal time they had to spend performing this task.

The “Fort Wolters Trumpet” was the weekly newspaper that allowed WOCs to learn of what was going on outside of their somewhat sequestered world. Charles “Chico” Alvarez and other WOCs volunteered to collect and contribute news and articles of interest about 67-5 for the “Trumpet.” The weekly column about the class had a firm deadline and everything written had to be vetted by Company cadre before it was submitted for publication. Seeing one’s name, or indeed anything positive in print about the “Green Hats” provided a valuable boost in morale and esprit de corps and helped compensate the writers for the valuable personal time they had to spend performing this task. On December 16th, 1966, WORWAC 67-5 were seated in alphabetical order at the Post Theatre for its graduation ceremony. In front of the invited family, friends and guests, the Post Commander Colonel E. P. Fleming, Jr., introduced Major General E. C. Dunn who gave the address to the graduates. The members of 67-5 then walked across the stage and received their diplomas from MG Dunn, with the ceremony concluding with a choral rendition of “This is My Country” by the Fort Wolters Candidate Chorus and the Benediction by Chaplain Jester S. Forrester.

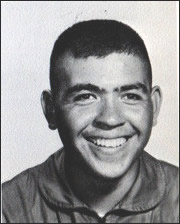

On December 16th, 1966, WORWAC 67-5 were seated in alphabetical order at the Post Theatre for its graduation ceremony. In front of the invited family, friends and guests, the Post Commander Colonel E. P. Fleming, Jr., introduced Major General E. C. Dunn who gave the address to the graduates. The members of 67-5 then walked across the stage and received their diplomas from MG Dunn, with the ceremony concluding with a choral rendition of “This is My Country” by the Fort Wolters Candidate Chorus and the Benediction by Chaplain Jester S. Forrester.  WO Charles A. Alvarez

WO Charles A. Alvarez  WO David L. Blattel

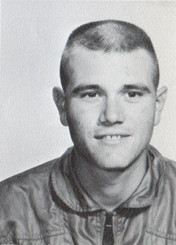

WO David L. Blattel  WO Thomas G. Carlisle

WO Thomas G. Carlisle  WOC James R. Carlson

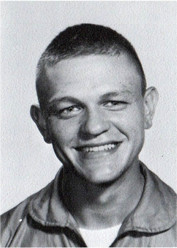

WOC James R. Carlson WO Terry R. Clark

WO Terry R. Clark  WO Charles M. Cotton

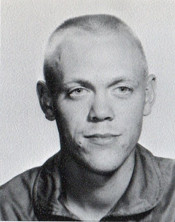

WO Charles M. Cotton  WO Robert N. Dechene

WO Robert N. Dechene  CWO Stephen J. Eckle

CWO Stephen J. Eckle  CWO Dennis C. Hamilton

CWO Dennis C. Hamilton  CWO Robert C. Link

CWO Robert C. Link  WO Ronald L. Martin

WO Ronald L. Martin  WO Donald B. Mc Coig

WO Donald B. Mc Coig  WO Larry S. Mc Kibben

WO Larry S. Mc Kibben  CWO Thomas J. Smith

CWO Thomas J. Smith  WO Russell L. Wallace

WO Russell L. Wallace  WO Jeffrey J. Yarger

WO Jeffrey J. Yarger